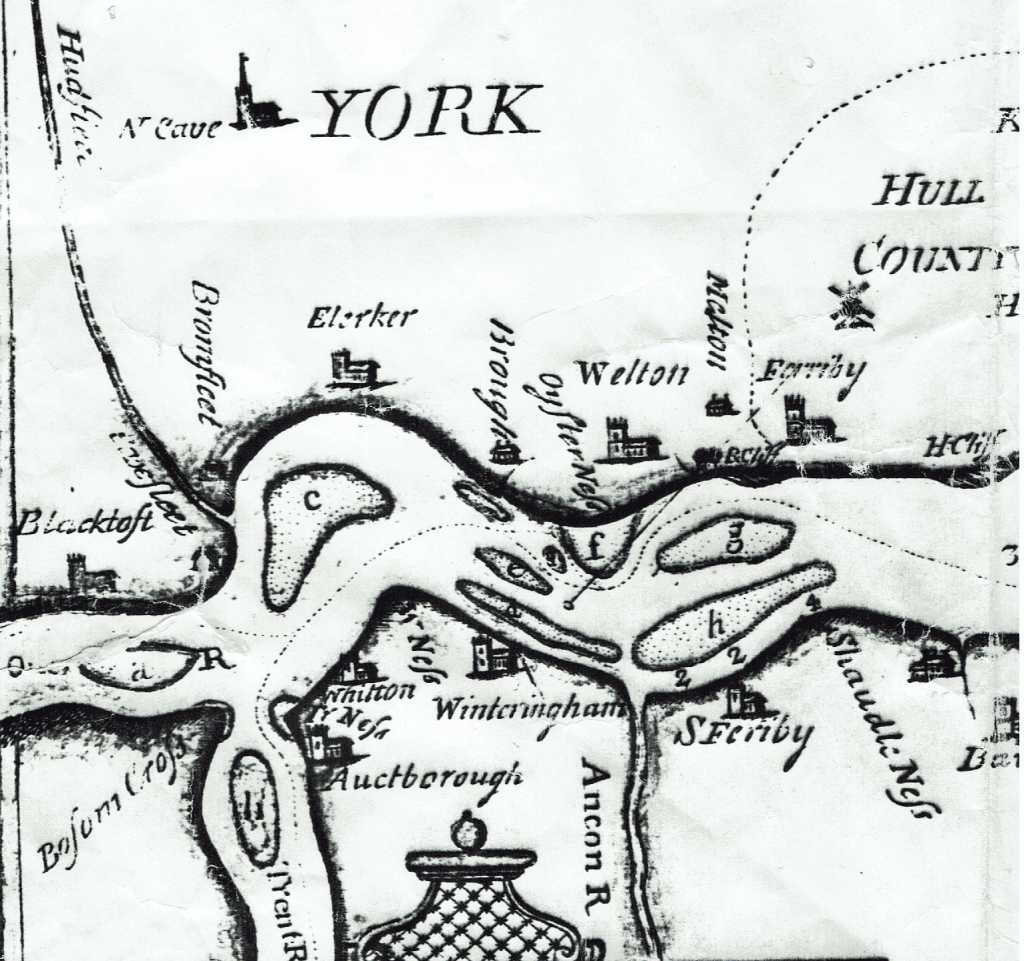

For today’s blog, and returning to the above theme, am showing an extract from John Scott’s navigational map of the Humber Estuary printed in 1734. Three or four further extracts will follow.

This section of Scott’s map shows the ‘upper’ Estuary (landward end). Scott’s navigational map was the earliest one to show details of the upper Estuary as well as the ‘lower’ (seaward end), this reflecting the focus on the port of Hull after the demise of the ports of Barton, Hedon and Ravenser Odd (lost to marine erosion) and before the creation of Goole Docks in the 1820s. Scott uses contemporary spelling for place-names and is reasonably accurate in his representations of the parish churches at that time.

Scott showed the ‘sands’ (mudflats), knowledge of which was essential to successful navigation, and names them in a key – a, on the left is ‘Ouse sand’, c is Whitton sand (still so today), f is ‘Oysterness sand’, d is Winteringham sand, e is ‘Paut sand’, h is ‘Old Warp sand’ and j is ‘Sudden Pye sand’.

It is clear from modern experience that mudflats grow and decline in all sorts of locations along the Estuary so, to an extent, Scott is only showing the situation as it was in the early 1730s. Some, however, seem to have been static over time, Whitton sands for example.

Besum Cross(?), bottom left, defines the point at which the River Don had once flowed into the head of the Humber.

The dotted line in the Estuary shows the best deep water channel for navigation, as in the 1730s. The three numbers below Old Warp sands shows the depth in fathoms in that channel.

Clearly a map such as this must have been surveyed across a period of time. The sands would have been visible at low tides, preferably spring tides, while a plumb-line could have been used to calibrate depths.